Why the iPad Pro needs Xcode

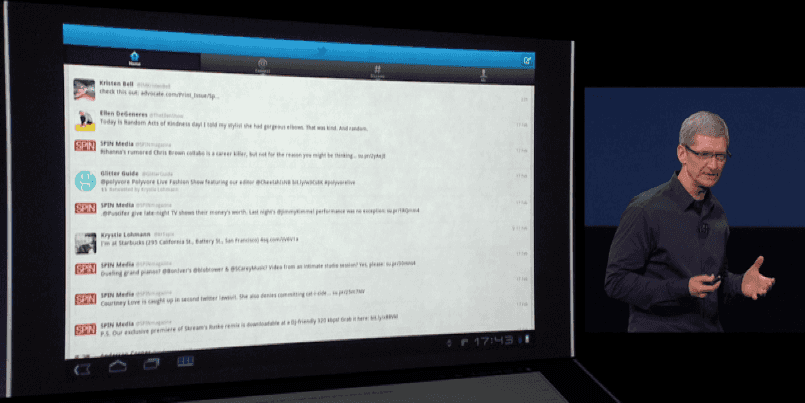

On March 7, 2012, Tim Cook announced their 3rd-generation “New iPad”, leading into it with a (fair and justified) dig at the state of Android tablet apps. Apps like Twitter and Yelp were shown as they ran at the time, with a smartphone-based UI stretched out to fit the wider display. Cook made jokes about apps being hard to see, with small text and lots of whitespace.

The prospect of building iPad apps has not been as popular for developers as building for iPhone. At the same time, iOS as a platform went from having a couple fixed screen sizes to requiring developers design their apps to be flexible. In an effort to bring more iPhone apps to iPad, Apple developed the concept of Adaptive UI, pushing developers away from targeting screen sizes to targeting flexible rectangles with certain size properties.

What Apple wanted to happen was that developers would build a compact UI, and a full-size UI, and the library of iPad apps would naturally expand to have a lot of what was on iPhone. But that didn’t really happen. What happened instead was that many developers design and target for iPhone, then fudge and fiddle with that UI until it looks okay on iPad, leading to (in the worst case) things like what Twitter’s iPad app has now become.